Healing Spatial Imagination Through Counter-Cartographic Practice (Part Two)

The visceral recognition I described in Part One creates more than intellectual understanding. When your body learns to feel the difference between extractive and generative approaches to place, you develop what I call "cartographic discernment" - the ability to sense whether spatial representations support life or diminish it.

Counter-cartographic practice isn't simply about critiquing harmful maps. It's about remembering ways of relating to place that honor the complexity of living landscapes.

The Persistence of Colonial Spatial Programming

The maps I examined in Part One weren't historical curiosities but foundational documents that shaped generations of spatial understanding. Finley's aggressive territorial boundaries continue organizing political relationships today. The hierarchical worldview embedded in educational atlases still influences how Americans understand their place in global contexts.

Colonial Map by Anthony Finley 1825 overlayed by Apple Maps GPS 2025, showcasing how colonial borders persist.

Most of us learned to navigate using maps that reduce living landscapes to abstract geometric relationships. We internalized ways of seeing that prioritize ownership over relationship, boundaries over flow, extraction over reciprocity. Breaking free from these inherited limitations requires conscious practice in developing alternative spatial relationships.

Developing Cartographic Discernment

Learning to distinguish between life-supporting and life-diminishing spatial representations develops through practice rather than theory. I've found several approaches particularly helpful.

First, spend time with maps that make your body feel uncomfortable. Notice what specifically generates unease - color choices, typography, how boundaries cut through natural features, absent indigenous place names. Pay attention to physical sensations rather than just intellectual observations.

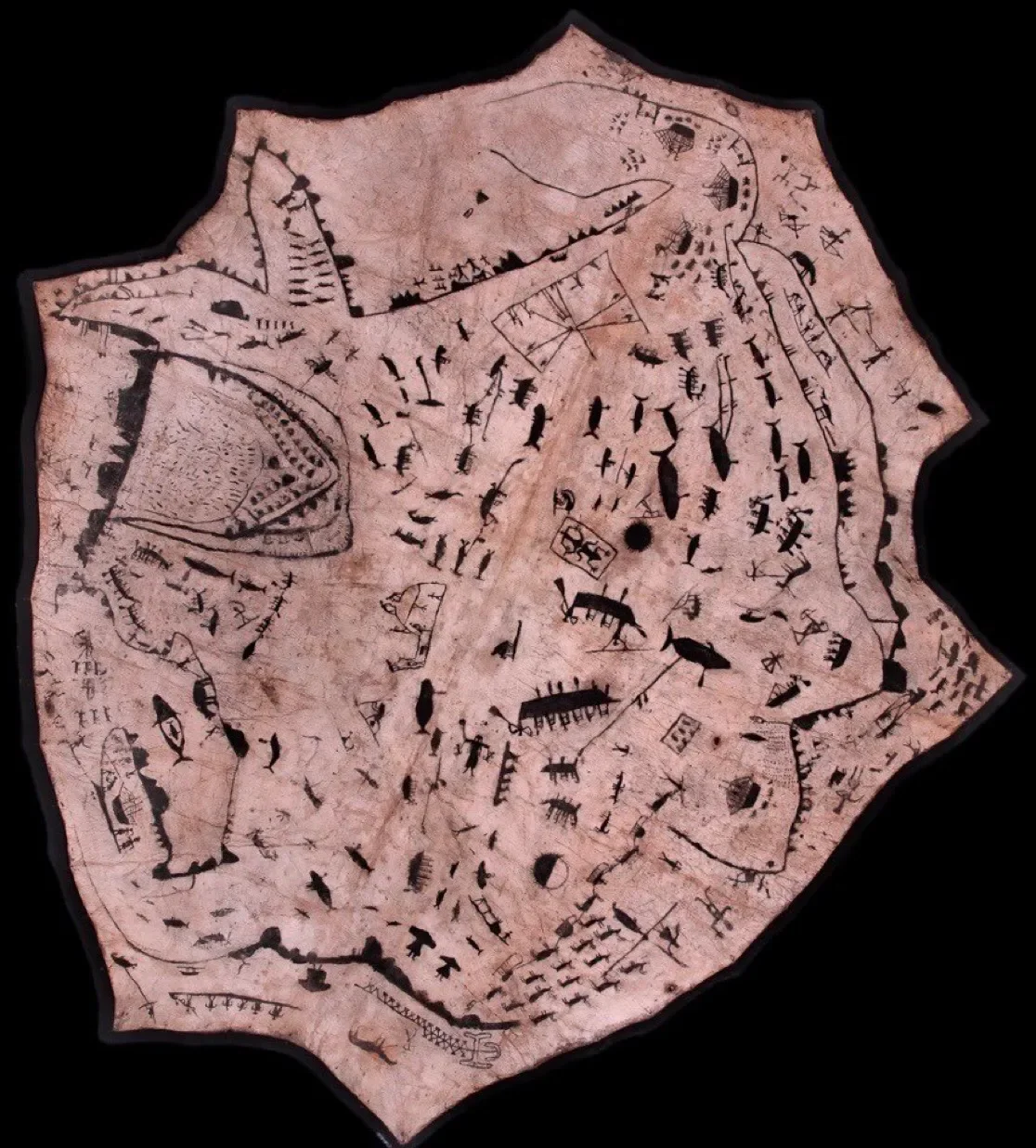

Next, seek out mapping traditions from cultures that maintained different relationships with place. Traditional Aboriginal songline maps encode spiritual geography alongside practical navigation. Polynesian stick charts represent ocean swells through tactile materials that connect navigators directly with maritime conditions. Inuit land maps integrate seasonal change, animal behavior, and spiritual relationships within single spatial representations.

When you see how indigenous mapping traditions integrate multiple dimensions of relationship with place, the reductive nature of territorial boundary maps becomes obvious.

Practicing Embodied Geography

Counter-cartographic work depends on developing direct relationship with the places we inhabit. This means learning to navigate using our bodies rather than just abstract representations.

During my desert camping experiences, I've been experimenting with what I call "embodied geography." Instead of relying primarily on GPS navigation, I spend time learning to read landscape features directly. Understanding how different rock formations indicate water sources, how plant communities change with elevation, how wind patterns shift throughout the day.

When you understand landscape through direct experience, territories stop feeling like possessions and start feeling like relationships. You begin to sense intricate connections between geological processes, plant communities, animal patterns, and seasonal cycles that colonial maps typically ignore.

Creating Alternative Spatial Narratives

Healing spatial imagination involves actively creating different stories about the places we inhabit. This means researching pre-colonial place names, understanding indigenous relationships with local landscapes, and learning about ecological patterns that existed before industrial modification.

Inuit Map of the Spirit Realm on Seal Hide

n my Southern Arizona context, this involves understanding Tohono O'odham nation relationships with the Sonoran desert that developed over thousands of years. Their agricultural practices, seasonal migration patterns, and sacred geography create entirely different spatial narratives than the territorial boundaries imposed during American colonization.

Cities like Phoenix were designed to erase evidence of Hohokam canal systems and settlements that had supported thriving communities for over a thousand years. Understanding these erasures helps explain why contemporary urban environments often feel disconnected from local ecological patterns.

Building Contemporary Counter-Cartographic Practices

Counter-cartographic work today involves both recovering traditional knowledge and developing new approaches appropriate for contemporary contexts.

Community and Participatory Mapping in Planning

The Native Land digital project demonstrates one approach by overlaying indigenous territorial information onto contemporary map interfaces.

My own practice through the Tarru Nadi collection involves curating historical maps that challenge colonial narratives while providing educational context about alternative cartographic traditions. The goal isn't promoting particular maps as perfect but expanding awareness of diverse approaches to spatial representation.

The Liberation Dimension

Counter-cartographic practice connects intimately with liberation movements because spatial control represents one of colonialism's most persistent tools. When we reclaim authentic relationship with place, we reclaim political agency that colonial spatial programming was designed to diminish.

Standing Rock water protectors weren't just opposing pipeline construction but challenging colonial assumptions about territorial ownership that made such projects possible. Their resistance included creating alternative maps that centered sacred geography and ecological relationships over extraction infrastructure.

Practical Steps for Spatial Decolonization

Developing counter-cartographic practice begins with paying attention to how different spatial representations affect your nervous system and expanding awareness of the places you already inhabit.

Start by creating personal maps of meaningful places using non-colonial approaches. Instead of focusing on property boundaries, map emotional territories, seasonal changes, or ecological relationships. Research the indigenous history of places you spend time in. Learn traditional place names and their meanings.

Practice navigation using embodied awareness rather than just technological tools. Learn to read weather patterns, natural landmarks, and seasonal cycles. Support contemporary indigenous mapping projects like Indigenous Mapping Collective that combine traditional knowledge with contemporary technology.

Beyond Resistance: Generative Cartographic Futures

Counter-cartographic practice ultimately moves beyond critiquing harmful maps toward creating spatial representations that support thriving communities and healthy landscapes.

Terra Forma

What might maps look like that center ecological relationships over property boundaries? How could cartographic representations integrate multiple scales of time, from geological deep time to seasonal cycles to daily rhythms? These questions invite experimentation with new possibilities.

The work of spatial decolonization creates opportunities for profound healing, both for human communities and for the landscapes that colonial mapping reduced to abstract territories. When we remember how to relate to place through reciprocity rather than extraction, we open pathways toward regenerative futures that colonial spatial programming made difficult to imagine.

The Continuing Journey

Healing spatial imagination represents lifelong practice rather than destination. Each time we choose embodied navigation over abstract representation, each time we learn indigenous place names, each time we understand landscape through ecological relationship rather than property boundaries, we strengthen alternative spatial possibilities.

The maps that made me feel sick with their extractive energy serve essential purpose by teaching discernment. But the real work lies in cultivating cartographic approaches that honor the complexity of living landscapes and support thriving communities across multiple scales of relationship.

Different maps truly do create different possibilities. The question becomes which possibilities we choose to cultivate through our daily practices of relating to place.

Explore decolonial cartographic perspectives: The Tarru Nadi Collection offers carefully curated historical maps that challenge colonial spatial narratives.

Read Part One: Green with Greed: Reading Colonial Psychosis in Historical Maps