Sacred Routes: Mapping Spiritual Safety During the Great Migration

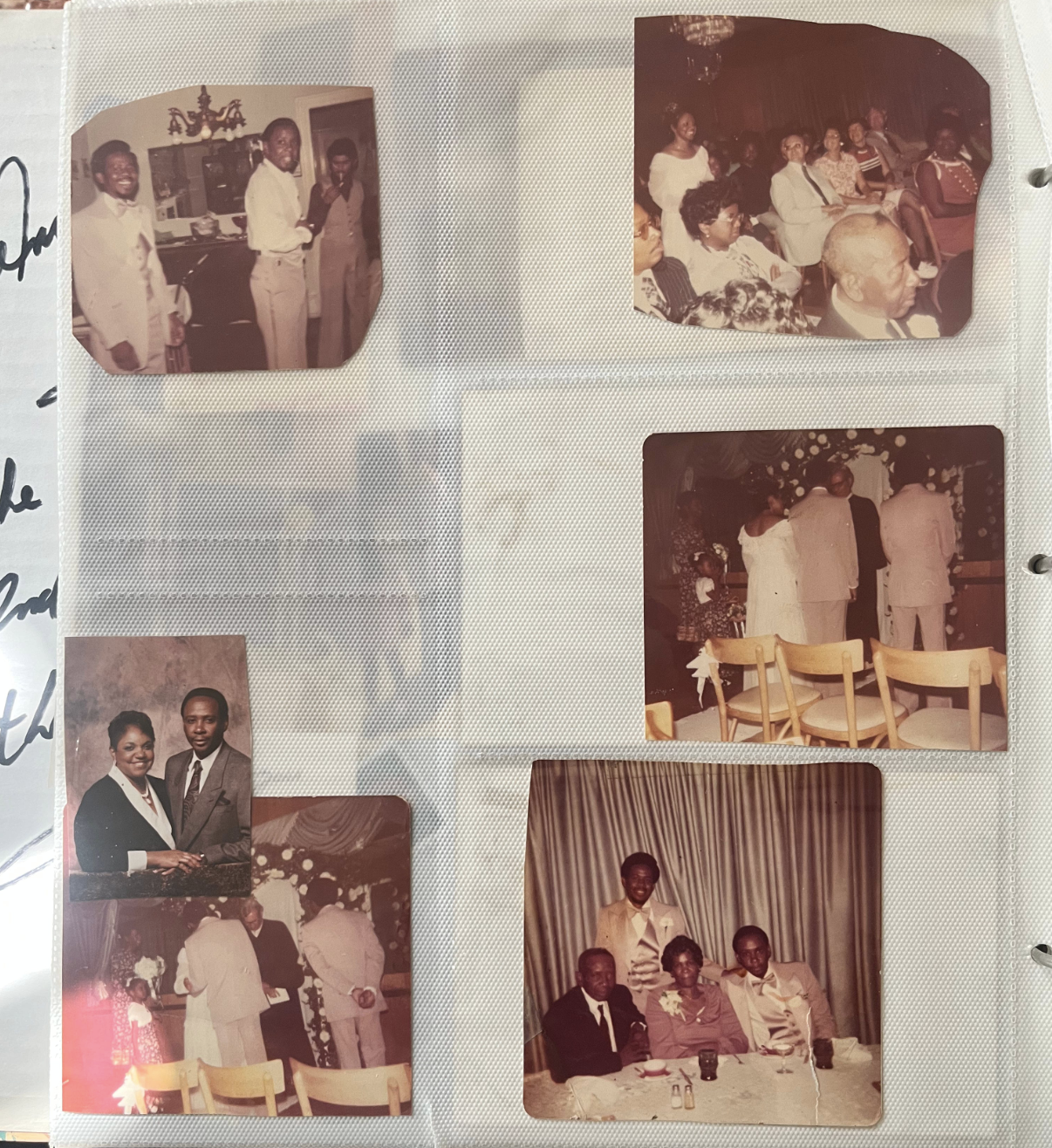

Last year while visiting home in Philly, I spent hours digging through my grandmother's vast collection of memorabilia. Every time I'm in her home I find myself engaging the same material that captivated me as a kid, but with fresher eyes. As I grow, my capacity to be with these stories deepens.

This time I discovered artifacts from South Carolina that I'd somehow missed during previous explorations. Quilts folded with mathematical precision. Photographs documenting family gatherings I'd never heard about. Pages of poetry from my grandmother's pursuit as a God-fearing poet. And there, wrapped in cloth that felt ancient to my fingers, little mojo bags that hadn't been energized for some time.

I immediately understood what these meant. My inheritance. Momentos from various extended family members' lives that had traveled north during the Great Migration, carrying not just memories but active spiritual technologies designed to protect and guide families navigating hostile territories.

These objects represented something far more sophisticated than nostalgic keepsakes. They were components of portable spiritual navigation systems that enabled Black families to maintain ancestral connections while crossing geographic boundaries that often meant leaving behind sacred sites and community support networks.

The Cartography of Spiritual Survival

Understanding how Black families maintained spiritual safety during migration requires recognizing that displacement from ancestral lands represented more than geographic transition. Traditional African spiritual practices often centered around natural forces that held particular spiritual significance. Fleeing the psychosis of White Supremacy also meant leaving behind sacred territories where generations of ancestors had established spiritual relationships with place.

While the Negro Motorist Green Book provided essential guidance for navigating hostile territories, it represented only one layer of sophisticated navigation systems. Parallel networks documented spiritual protection routes and practices that enabled families to maintain connection to ancestral wisdom despite displacement.

Families couldn't pack the oak tree where great-grandmother spoke with ancestors, but they could carry roots from that tree. They couldn't transport the creek where healing rituals took place, but they could preserve stones from its bed. These objects became spiritual anchors, maintaining connection to ancestral wisdom as external circumstances shifted dramatically.

Conjure and hoodoo traditions provided frameworks for creating protection that didn't require elaborate ceremonies or permanent altars, making them perfectly suited for families living in temporary housing or under hostile surveillance. The spiritual displacement created urgent need for portable protection systems that could function across geographic boundaries.

Ancestral Technologies in Transit

Mojo hands and conjure bags represented the most sophisticated portable protection technologies enhanced during this period. These small cloth bundles contained carefully selected combinations of roots, stones, herbs, and personal objects charged with specific protective intentions. Unlike European religious practices requiring institutional buildings, these spiritual tools placed protective power directly in individual hands while maintaining connection to ancestral wisdom.

The creation of mojo hands required intimate knowledge of botanical properties, seasonal timing, and spiritual correspondences preserved through oral tradition despite centuries of disruption. Families traveling north carried not just physical objects but knowledge systems necessary to maintain and renew their protective power.

What strikes me most about these spiritual technologies is how they anticipated challenges Black families would face in urban environments. The protection wasn't just against physical harm but against psychological assault of hostile territories, spiritual isolation from ancestral lands, and emotional toll of navigating systems designed to deny their humanity.

Traditional African American folk medicine integrated spiritual protection with physical healing, understanding health as relationship between individual well-being and spiritual alignment with ancestral wisdom. Families carrying healing roots and protective herbs maintained access to healthcare systems that functioned outside white medical institutions that often denied them service and experimented on them.

The discretion required for maintaining these practices in hostile territory influenced their development significantly. Protection needed to be invisible to potentially dangerous observers while remaining accessible to family members who understood their significance. This led to innovations like incorporating spiritual objects into everyday items and developing coded language for discussing spiritual matters in public spaces.

Networks of Spiritual Knowledge

While the Green Book documented safe spaces for physical survival, parallel networks shared information about spiritual practitioners and sacred spaces that could support families' spiritual well-being in new territories. These networks operated through kinship connections, church affiliations, and workplace relationships among migrating communities.

Beauty salons and barbershops functioned as crucial nodes in these spiritual information networks. Beyond social gathering spaces, these businesses often employed practitioners who maintained traditional knowledge about spiritual protection and herbal medicine. The intimate nature of personal care services created opportunities for private conversations about spiritual matters that couldn't safely occur in more public settings.

Churches provided another layer of spiritual networking, though the relationship between traditional African spiritual practices and Christian institutions remained complex. Progressive ministers sometimes incorporated traditional healing wisdom into Christian frameworks, while families often navigated multiple spiritual systems simultaneously.

Women's networks proved particularly crucial for preserving and transmitting spiritual knowledge during migration. Traditional healing wisdom often passed through maternal lines, and women maintained responsibility for family spiritual protection even as they adapted to wage labor and urban living. Domestic workers who traveled between neighborhoods served as crucial communication links, sharing information about practitioners and resources across geographic boundaries.

Urban Adaptations and Innovation

The transition from rural to urban environments required significant adaptation of traditional spiritual practices. Apartment living meant families couldn't maintain elaborate altars or practice rituals requiring outdoor spaces, leading to innovations in creating sacred space within constrained physical environments.

Salt became particularly important in urban spiritual practice because it could serve multiple protective functions while appearing completely ordinary to potentially hostile observers. Traditional use of salt for spiritual cleansing adapted to urban applications like washing doorways, sprinkling around beds, and adding to bathwater for protection. This dual functionality made it perfect for families needing to maintain spiritual practices while avoiding suspicion.

Plant medicine traditions adapted to urban availability by incorporating medicinal herbs available in city markets, often through connections with other immigrant communities who maintained their own traditional healing practices. This led to cultural exchanges where Black families learned about European medicinal plants while teaching other communities about African healing traditions.

The development of apartment-based altar practices represented remarkable innovation in sacred space creation. Traditional altars often occupied central positions in homes with elaborate arrangements. Urban altars needed to be portable, discrete, and functional within limited space while maintaining spiritual effectiveness. This led to practices like creating temporary altars for specific rituals and incorporating spiritual objects into everyday household arrangements.

Water presented particular challenges in urban environments where access to natural water sources was limited. Urban adaptation required finding ways to charge ordinary tap water with spiritual intention or locating urban water sources that could serve ritual purposes. Some families maintained connections to rural water sources by carrying water from ancestral territories during visits home.

Continuing Legacy

The portable spiritual technologies that families carried north provided foundation for reconstituted sacred spaces that Black communities created in Northern and Western cities. The innovation required to maintain ancestral wisdom under hostile conditions generated spiritual practices that continued evolving throughout the 20th century, influencing contemporary approaches to spiritual resilience and community protection.

The objects I discovered in my grandmother's collection represent links in an unbroken chain of spiritual technology that enabled families to maintain protective practices while building new forms of community support in urban environments. These weren't museum pieces but active components of spiritual systems that continued functioning across generations.

Understanding these sacred routes helps us appreciate the sophisticated survival systems that enabled not just physical migration but spiritual continuity across one of the most traumatic displacements in American history. The spiritual innovations developed during the Great Migration continue offering guidance for contemporary practitioners seeking to maintain traditional practices within modern constraints while building community connections that support both individual and collective spiritual development.

The maps my grandmother's family carried weren't documenting streets or highways but spiritual territories where ancestral wisdom could take root in foreign soil. Their innovations in portable sanctuary creation demonstrate how spiritual technologies can transcend geographic boundaries while maintaining connection to traditional sources of power and wisdom.

This exploration builds on themes introduced in "The Cartography of Sound: Black Musical Traditions as Spatial Technologies", examining how communities created portable systems for maintaining cultural continuity during geographic displacement. Next week, we'll investigate how these spiritual technologies evolved into the sacred spaces that anchored Black communities in urban environments.